Balancing the Needs of People and Wildlife: An Integrated Approach to Conservation and Development in Rwanda

Smart Green Village, Rwanda.

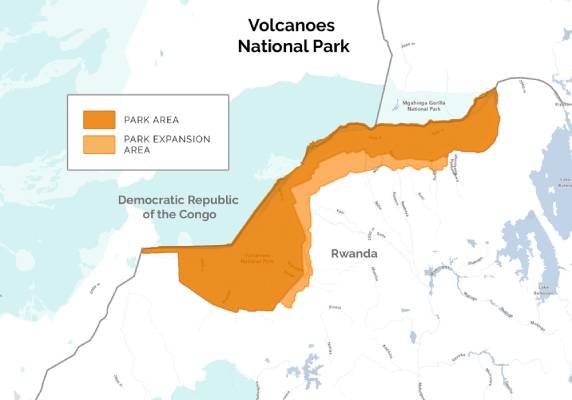

The rebounding of the gorilla population in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park (VNP) is one of conservation’s great success stories. But with that success comes a new challenge: limited space that gorillas and people must share.

Volcanoes National Park.

Rwanda is one of Africa’s most densely populated countries, with farmland directly abutting the park. The needs of gorillas and people are colliding. In response, AWF is partnering with the government of Rwanda to develop a “master plan” for the region. This plan, which supports Rwanda’s green economy and defines land use and investment, is crucial in creating long-term resiliency and opportunity for people living around Volcanoes National Park—while ensuring the park has enough space to support the growing gorilla population.

Patrick Nsabimana, AWF Rwanda Program Manager and Acting Country Director is leading AWF’s work with local communities in the country, advancing a pilot program launched as a proof of concept for the overall master plan. We recently spoke with him to better understand how a community-led conservation approach drives the strategy, paying off for both people and wildlife in Volcanoes National Park and the surrounding communities.

Q: What is the long-term vision of AWF’s partnership with the Rwanda government?

Nsabimana: The collaboration creates a model for how conservation can be the engine for sustainable development and poverty alleviation. By aligning with Rwanda’s national priorities, such as Vision 2050 and the Green Growth and Climate Resilience Strategy, we’re contributing to the country’s broader development goals while safeguarding its unique natural heritage.

The partnership is also important because it represents a holistic approach to addressing some of the most pressing challenges of our time—biodiversity loss, climate change, and sustainable development. We hope to achieve nothing less than a transformation in how we think about and practice conservation, one that puts communities at the center and demonstrates the intrinsic link between healthy ecosystems and human prosperity.

Q: What are the goals for the program?

Nsabimana: We are working to integrate conservation and development outcomes through coordinated landscape-level planning and investment. This includes developing and implementing a participatory land use plan for the Volcanoes National Park (VNP) landscape by 2026, expanding the habitat for endangered wildlife populations in VNP, and ensuring that relocated communities in the landscape have sustainable diversified income sources and increased economic opportunities. But most importantly, we hope to create a replicable national model that demonstrates how conservation and development can be mutually reinforcing. This could have far-reaching implications not just for Rwanda but for other countries facing similar challenges.

Gorilla near Volcanoes National Park.

Q: How does the program partner with and include communities living near Volcanoes National Park?

Nsabimana: Extensive community meetings and engagement have taken place across affected communities, involving over 500 community members, allowing us to gather local perspectives, address concerns, and incorporate community input into our planning. This process has been crucial in securing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in identifying and restoring land for gorilla habitat.

We have also established community representation in decision-making. For instance, project-involved people have elected 24 community-level representatives to liaise on issues relating to securing land for restoration to the park and helping the community move to the new neighborhoods, which are being designed to meet people’s needs for climate-resilient housing, electricity and sanitation, access to health care and education, and the like. We’ve also set up community committees to advise us on concerns directly related to the overall pilot project.

Q: What does Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) mean in the context of this program and what are your biggest challenges?

Nsabimana: FPIC, in our context, means that local communities have the right to get comprehensive information covering the nature, size, pace, reversibility, and scope of the proposed project, its duration, and the affected communities. This involves consultations and participation in good faith, allowing communities to approve or reject the project based on a collective decision-making process.

Implementing FPIC comes with significant challenges such as addressing diverse stakeholder interests, managing community expectations, adapting to changing community needs over time, and ensuring that consent (or lack thereof) is properly documented and verifiable. Despite these challenges, FPIC is a fundamental principle of this program, and AWF is ensuring genuine community consent and participation in the process.

Free, Prior, and Informed Consent refers to the right of Indigenous Peoples to give or withhold their consent for any actions or activities that would affect their lands, territories, or rights.

Q: What are the community’s greatest needs and how are you helping meet them?

Nsabimana: One of the greatest needs is for diversified, sustainable income sources. Many households rely on subsistence agriculture, which can lead to pressure on park resources. We sat down with community members with the intention to build economic opportunities. The result is a comprehensive Livelihood Improvement Plan that introduces 17 new livelihood options designed to grow the economy around climate-resilient and conservation compatible activities. Community members will be supported with training, start-up capital, and market linkages that are projected to increase household income by up to 30%.

We’ve also recognized the need for targeted support for women and youth. Our enterprise development initiatives aim for 30% women-owned and 20% youth owned businesses.

Other needs include improved access to health care, education, water, and sanitation. Our modern green neighborhood concept addresses this by incorporating health centers, early childhood facilities, and improved water and sanitation systems. While still in the planning stage, this initiative aims to significantly improve people’s quality of life.

Due to land scarcity, crop raiding by wildlife is a significant concern. We’re working on strategies to reduce human wildlife conflict, including buffer zone management, and exploring alternative livelihoods that are less vulnerable to wildlife damage. As we restore parts of the park and develop the green neighborhoods, we are working for fair compensation and livelihood restoration for affected households living in areas identified as best suited to wildlife habitat. And we are ensuring they can relocate to modern neighborhoods that improve living conditions and economic opportunities.

Q: What recent strides have you made through the livelihood enhancement programs?

Nsabimana: Through a partnership with Inkomoko, an NGO that provides business expertise and access to financing for entrepreneurs, we launched an innovative business incubation program to empower local entrepreneurs to develop sustainable business enterprises. In July, our first cohort of 100 entrepreneurs attended a workshop focused on developing business plans and equipping participants with essential skills for success. This program offers comprehensive support in training and mentoring, start-up funding, and infrastructure access. By fostering local ownership and building resilience, we’re creating a win-win scenario for both wildlife and communities.

Q: What makes you hopeful?

Nsabimana: The high level of community participation is incredibly encouraging. Over 500 community members actively engaged in our meetings, showing a genuine interest in shaping the future of their landscape. In addition, the strong support and collaboration we’ve received from the Rwandan government gives me confidence that our efforts align with national priorities and will have long-term support.