Cross-border communities join hands to restore Faro’s green wild lands

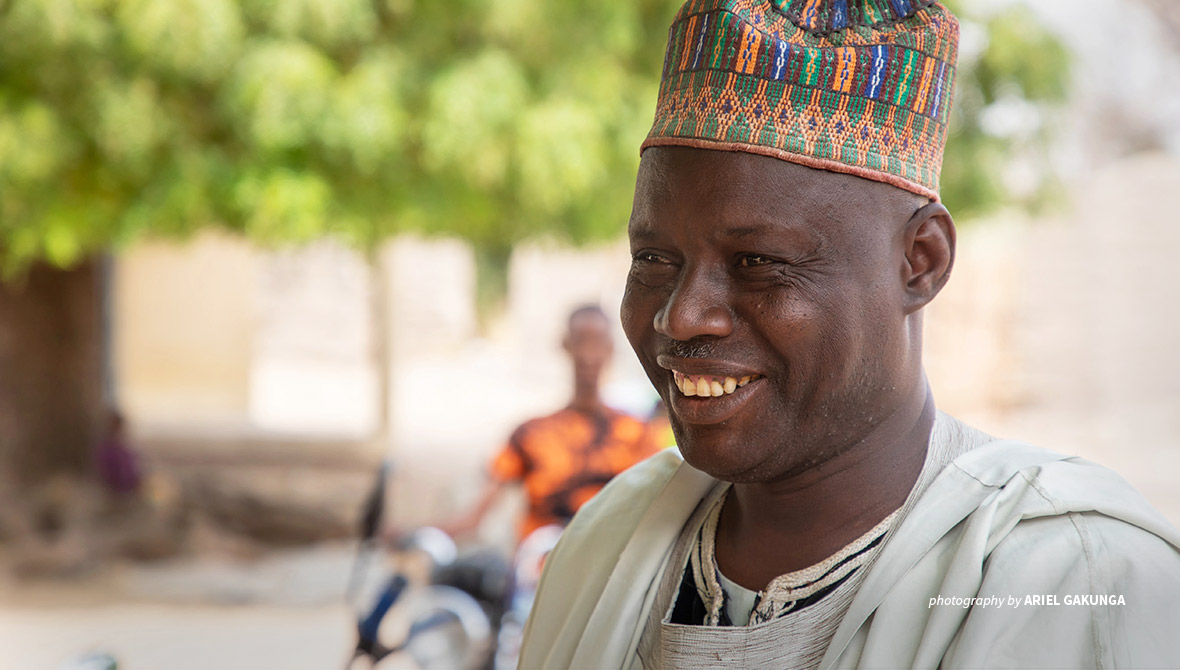

Mohamadou Ahmadou grew up in Northern Cameroon, and now leads awareness campaigns to mitigate overgrazing impacts around Faro National Park

Mohamadou Ahmadou never imagined that River Faro, the gushing tributary of the Benue that his parents forbade him and his siblings from swimming in, would one day fill with sand and dry up in some sections. Growing up in Tchamba, Northern Cameroon in the early 2000s, he would not have thought that the green bush lining the Tchamba-Voko road would someday become nothing but barren land, with countable trees, emptied of the wildlife he would spot while traveling along the road on camelback with his father.

Faced with the evidence of harsh climatic conditions in the region, Mohamadou cannot help but sigh. At first, nobody in his community understood that cutting trees for the construction of huts and firewood would seriously impact their environment. Mohamadou’s father was a herder who, along with many others, had fled the scorched lands of the Mandara mountains in the Far North to settle in the south, where the climate favored grazing and agriculture. Mohamadou, who was 10 back then, describes the delight on the faces of the dottidjos (elders) when they came across the “greenness” in Faro.

They fed their cattle to satisfaction till there was no more grass, and then, they turned to the remaining trees and cut them for fuel. As both human and livestock populations grew, so did the need for pasture and farmland. They knew that Faro National Park was a protected area — one should not venture in for pasture — but what did protection matter when there were hungry cows? Soon, herders from Nigeria, Central Africa, Mali, and Niger who had run out of grazing land in their countries also discovered the utopia in Cameroon, and slowly the bountiful Faro oasis crumbled.

Today, the movement of large herds of livestock from one grazing land to another — cross-border transhumance — is one of the biggest resource conflicts in the region. It has led to dwindling pasture and farmlands, aggravating the already existing conflicts between farmers and herders in the region, and has even created new disputes.

Mohamadou explains: “My village, for example, shares a border with the Faro National Park, which is a protected area. Apart from us herders and the farmers who live there, wild animals still consider this their home. The farmers and herders are already at loggerheads. When other herders come in from Nigeria, our relations grow tenser as we constantly fight over land for grazing or farming. The wildlife also suffers because some of them are hunted for food and money. Some people even bypass conservation agents and go into the park with their cattle.”

Security risks are further compounded. “As the herders move along with their cattle, it attracts cattle raiders and kidnappers," Mohamadou notes.

Apart from transhumance, demographic explosion, climate change, insecurity, infrastructure development, and increased agricultural exploitation also make up the list of pressures exerted on the landscape. Faro National Park, which was once sacred, is now an invader’s paradise.

Overgrazing degrades biodiversity hotspots like Faro

Addressing transhumance in the Faro landscape

But all is not lost. Mohamadou knew it was possible to conserve the Faro landscape and restore it to its former glory, but he did not know where to begin until the African Wildlife Foundation set up an office in the landscape. AWF’s Community Development Officer in Faro, Adamou Aboubakar, introduced Mohamadou, alongside nine other men and two women, to the TANGO concept — a community-based initiative designed to reduce illegal incursions of transhumant herds into protected areas to protect wildlife and its habitat and simultaneously reduce human conflicts.

“TANGO involves an effective and suitable two-way communication between protected area authorities, local communities, and incoming transhumant herds for the peaceful management of transhumance and the respect for transhumance corridors and wildlife, says Adamou.

Through this initiative, TANGO teams deployed throughout the landscape work in collaboration with AWF and the Cameroon Conservation Service to collect and share information as well as track transhumant movements and their positions in and around the Faro National Park. They also assist us in sensitizing local populations on how to mitigate conflicts associated with transhumance,” Adamou adds.

In three months, Mohamadou and his TANGO team have recorded great success. They have engaged up to 730 men and about 350 women on the peaceful management of transhumance in local communities and amongst transhumant herders in Faro and Nigeria. Also, the once-strained relations between Nigerian herders and Cameroonian farmers and herders have significantly improved due to TANGO sensitizations. Nigerian transhumant herders are even demanding the extension of TANGO operations in their country.

Apart from addressing issues related to transhumance, AWF, via the European Union's Preserving Biodiversity and Fragile Ecosystems in Central Africa program (also known as ECOFAC 6), also works with the wildlife management authority of the Faro National Park to tackle commercial poaching as well as illegal fishing and gold mining in and around the protected area.

As AWF's Community Development Officer in Faro, Adamou Aboubakar participates in regional stakeholder meetings

Collaborating to deliver Faro’s conservation agenda

Mohamadou is not the only one concerned about transhumance in Faro. Awe Central, the Conservator appointed by Cameroon’s Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife to Faro, regularly brings together traditional leaders, local community members, administrative authorities, and representatives of transhumance associations on both sides of the Cameroon-Nigeria border. Together, they discuss the management of cross-border transhumance flows between both countries and strategies for stakeholders to collaborate for the effective management of the Faro landscape.

The latest meetings were organized in March 2022 with support from AWF. At both the 5th Great Faro-Nigeria Bloc Conference on Transhumance and the 5th Faro Stakeholders Forum, participants were called upon to actively engage in and support conservation efforts in the Faro.

“Using the concept of participatory governance, which aims to create the conditions for organized power and collective action, we are working to make sure that the interests of the different parties are taken into account and the protected area is not just seen as a means of conservation of natural resources but also, as an opportunity of sustainable livelihoods for the communities,” says Conservator Awe Central.

Despite facing challenges, stakeholders in the Faro are committed to working together to ensure the conservation of their landscape and the elimination of the threats impeding peace and progress in the transboundary area.

“There is hope for the restoration of our beautiful landscape, our rivers, trees, and wildlife. That hope lies in conservation. I know that all will be well again because not long ago, I saw this beautiful, tall giraffe sneak its head out from the bushes to watch a vehicle pass on the road,” Mohamadou recounts. That image will forever rest in my mind and anytime I think of it, I smile. That picture alone gives me hope.”

> Learn more about AWF's European Union-supported conservation programs in the Faro landscape