Strengthening bonobo conservation through satellite technology

Compared to Africa’s other great apes, the bonobo has been relatively less studied. Its geographic range stretches 500,000 square kilometers across the Democratic Republic of Congo’s remotest tropical forests — difficult-to-reach areas with a history of regional political unrest. As such, research on bonobo ecological preferences, habitat use, and distribution has been mostly limited to small areas accessible by foot. However, with increased pressure from hunting and habitat degradation facing this endangered great ape, further study has become increasingly critical. Poaching and forest loss increased dramatically between 1990-2003 when civil conflict and two wars forced civilians to move into the forest's remote interior, where they cleared small areas for settlement and subsistence farming. These communities were already poor and depended highly on the forest for their livelihoods; the displacement caused by the wars increased their reliance on the surrounding forest ecosystems. Many began to hunt bonobos for bush meat despite both traditional taboos and national laws against hunting bonobos. Satellite imagery of Iyondji Community Bonobo Reserve, a protected area in Maringa-Lopori-Wamba, show an increased prevalence of forest clearings during the decade of civil conflict. The bonobo population in Luo Scientific Reserve declined by half between 1991 and 2005, and three groups disappeared completely.

While commercial logging and industrial agriculture are low in this remote landscape, an increase in local-scale agricultural activities is primarily responsible for forest fragmentation — the breaking up of intact forest blocks into smaller patches. Forest fragmentation poses a significant threat to bonobo conservation as disconnected patches increase vulnerability to hunting and isolate wildlife habitat, inhibiting genetic exchange between populations. At the same time, the illegal great ape trade continues to grow as new trade routes emerge to deliver bush meat to consumers.

Assessing habitats using satellite imagery

Fragmentation and other threats to bonobo populations — forest conversion to agriculture and roads, as well as human encroachment into forests — can be mapped using long-term satellite imagery. Integrated with detailed information from ground surveys, the systematic spatial data acquired from the imagery enabled us to develop models that predicted levels of hunting pressure and habitat degradation across the great ape’s range.

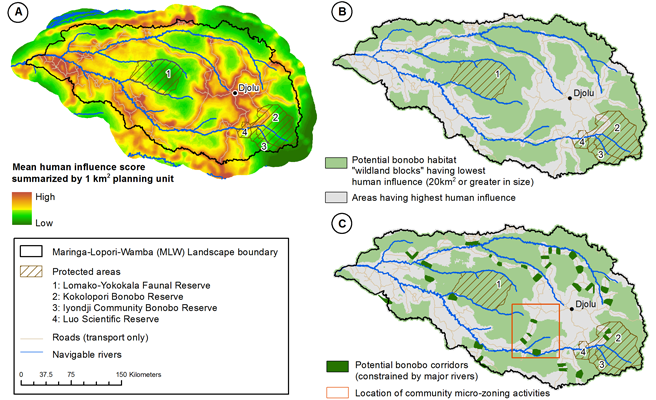

Both human accessibility as well as the relative population demand for bush meat influence the level of hunting pressure. We estimated human accessibility across the Maringa-Lopori-Wamba landscape considering factors like proximity to human settlement, roads and navigable rivers, and determined the ease of travel through land cover types. Our estimate of habitat degradation weighed a variety of factors impacting the quality of habitat — particularly the influence of agricultural and urban areas, logging roads, and industrial plantations.

Our results reveal that areas of highest human influence are clustered around roads where settlements occur. Areas less disturbed by human activity — designated as wildland blocks — suggested a higher potential for bonobo conservation. Taking into account the 20 square kilometer home range of the species, we identified 42 wildland blocks as important for species dispersal and connectivity that span 60 percent of the landscape.

Maintaining connectivity between wildland blocks facilitates wildlife movement and feeding across multiple habitat types and reduces inbreeding. We identified potential bonobo linkages by modeling 32 potential routes spreading across agricultural areas with human settlement that comprise 3 percent of the landscape. The identification of vulnerable priority conservation areas using spatial data can inform targeted conservation action to reduce hunting pressure and habitat degradation on the ground. Working closely with forest management authorities as well as local communities, African Wildlife Foundation relies on spatial maps for collaborative land-use zoning at the village scale to protect wildland blocks and bonobo linkages.

Nackoney, J., J. Hickey, D. Williams, C. Facheux, T. Furuichi, and J. Dupain. (2017). Geospatial information informs bonobo conservation efforts. In: Bonobos: Unique in Mind, Brain, and Behavior (B. Hare and S. Yamamoto, Eds.). Oxford University Press.

Securing a future for the bonobo

To prioritize forest protection for connected and viable populations of the bonobo, conservationists need a wider understanding the environmental conditions that support the species as well as where such conditions occur throughout its range. With collaboration from a large team of bonobo researchers and spatial modelers, we created a statistical model to identify the areas that have the most favorable environmental conditions for the bonobo across its geographic range using field observations of bonobo sleeping nests. These included abiotic factors and metrics for forest cover, agriculture, and human settlement extracted from satellite data.

The resulting map predicted approximately 28 percent of the range to be suitable. Of this area, 42,980 square kilometers are located in official protected areas. However, at least 54 percent of the potentially suitable land area has not yet been surveyed. Using the map, 14 future high-priority bonobo survey areas have been identified. While these areas may already be supporting previously unknown populations, the forests are also vital for the natural expansion of the ape’s current distribution. In the northern Maringa-Lopori-Wamba landscape, AWF has used the map to earmark a highly suitable location for a proposed new protected area.

The statistical model also suggested that bonobos avoided agricultural and forest edge areas and favored areas with dense, intact forest when making nests. In fact, threats associated with human activity have a greater impact on the ape’s distribution than biological or climatic conditions. As AWF’s community-based conservation efforts progress, this location-specific information can be updated over time, providing new ways to visualize the geographic relationship between human livelihoods and natural resource use.

This article is adapted from a chapter written by AWF researchers and collaborators in the recently released book Bonobos: Unique in Mind, Brain, and Behavior.