Why Collaring Lions Enhances Conservation and Coexistence

A pride of lions inside the Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, part of the Tsavo landscape in Kenya.

As dawn breaks over Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, the expansive Tsavo landscape in Kenya awakens. Spanning over 48,000 square kilometers – nearly twice the size of Rwanda – the Tsavo landscape’s vast savannah grasslands, volcanic hills, and riverine forests host approximately one-fifth of Kenya’s African lion population. Lions in Tsavo face mounting threats, including escalating human-wildlife conflict, habitat loss and fragmentation, inadequate prey, and poaching, among others.

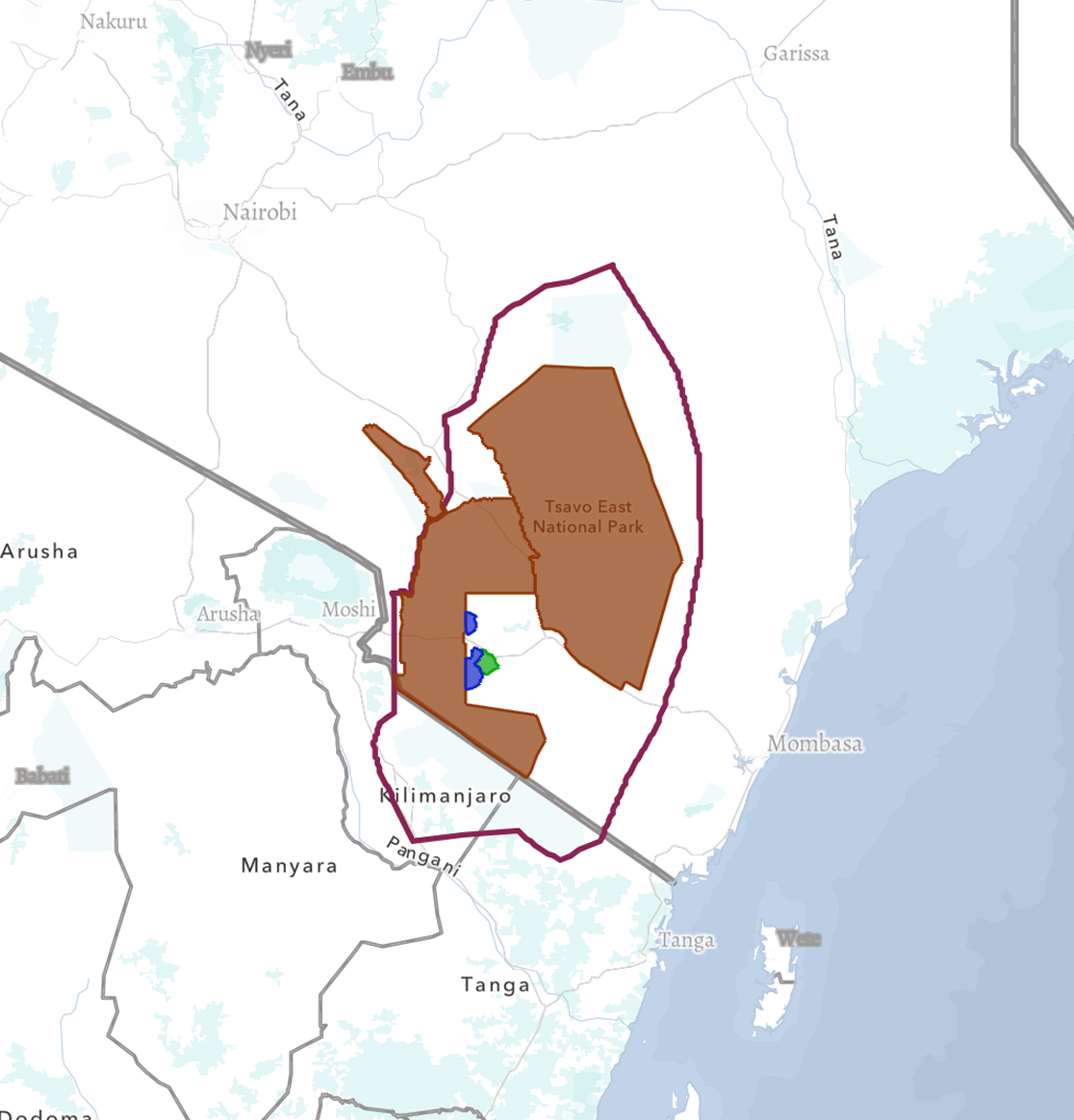

Tsavo-Mkomazi Landscape.

In September, Douglas Kamaru, an African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) Charlotte Fellow and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wyoming, embarked on a mission to collar five lions in Tsavo. This is part of a study examining prey depletion and its cascading effects on lions in the landscape. Using GPS collars, Kamaru aims to gather real-time data that can mitigate human-lion conflict and inform effective conservation strategies.

After days of patient tracking, Kamaru, accompanied by rangers and local conservancy scouts, spotted a pride of three lionesses with six cubs concealed within the tall grass and shrubs. With overcast morning weather blanketing the conservancy, their tawny coats blended seamlessly with the golden savannah, embodying nature’s camouflage.

Guided by an experienced Kenya Wildlife Service veterinarian, the team drove steadily toward the pride, the Land Cruiser’s engine purring softly to avoid startling the lions. Halting at a respectful distance, the veterinarian raised the tranquilizer dart rifle, his focus sharp and unwavering. With a precise shot, the dart hit the lioness on her left rib with pinpoint accuracy. Immediately her pride scatters.

As the sedative began to take effect, the team moved with speed, blindfolding the lioness to minimize her stress. Working carefully, the team helped Kamaru record vital data—her weight, teeth condition, and paw dimensions—to aid monitoring over the years. Finally, the team secured a GPS collar around her neck, a device designed to reveal her movements, hunting patterns, and interactions within the ecosystem.

A wildlife veterinarian takes a lioness's vital measurements during a collaring exercise in Tsavo Landscape, Kenya.

After 40 minutes, the procedure concluded with the administration of a reversal drug. From a safe distance, the team watched as the lioness woke, reoriented herself, and rejoined her pride.

A wildlife team monitors a sedated lioness during a GPS collaring operation in Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, Kenya.

Why Collaring Lions Matters

The low lion density in Tsavo—approximately 1.8 individuals per 100 square kilometers—is a cause for concern. Such scarcity indicates potential challenges with prey availability and habitat quality.

“Not much is currently known about Tsavo’s lions, which is why we’re fitting them with GPS collars,” Kamaru explained. “The collars will provide high-resolution data on movement and habitat use, allowing us to determine their home ranges and track their movements. In this area, we know of about four prides, including the one we just collared.”

Measuring the lioness claws.

“Prey depletion and land degradation may be having a domino effect on the lions in Tsavo,” Kamaru noted. “As prey becomes harder to find, lions may travel greater distances, increasing the likelihood of human-lion conflict. This conflict often leads to retaliatory killings, further threatening the population.”

GPS collars are revolutionizing wildlife conservation by providing real-time data. These collars not only track the lion’s movements but also incorporate geo-fencing alerts that notify rangers when collared lions approach human settlements. This allows rangers to warn communities and deploy scouts to prevent potential conflicts.

Philip Muruthi, AWF’s Vice President for Species Conservation and Science, underscored the significance of this approach. “Understanding where lions roam, find mates, and hunt allows us to develop and implement data-driven land-use plans with stakeholders, including local communities, conservancies, the private sector, and government authorities to balance conservation and human needs,” he said.

AWF has successfully implemented similar collaring projects in Tanzania’s Maasai Steppe, LUMO conservancy in Tsavo, and Zimbabwe’s Middle Zambezi, with promising outcomes in reducing human-lion encounters and fostering coexistence.

Despite being Kenya’s second-largest lion population stronghold after Maasai Mara, Tsavo is struggling to meet the criteria of a viable lion stronghold—defined as a habitat with over 500 lions and a stable or growing population.

“Our goal is to restore Tsavo as a lion stronghold now and in the long term,” Kamaru emphasized. “This research is crucial because it directly informs management strategies and policies for better conservation of lions and their prey.”

As apex predators, lions are essential for maintaining ecological balance. They regulate prey populations, preventing overgrazing and preserving biodiversity. However, with only about 24,000 lions remaining in Africa—a 75 percent decline over the past 50 years—the species is classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“Without lions, entire ecosystems can collapse,” Kamaru warned. “While lions are our primary focus, we’re also studying other large carnivores, such as leopards and cheetahs, to understand broader conservation challenges.”

Muruthi adds, “Collaring will allow us to better understand lion behavior, including predation, and to estimate numbers.”

Douglas Kamaru helps prepare a GPS collar for a lioness in Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, part of the Tsavo landscape in Kenya.

Compounding Threats: Climate Change and Human Activity

Conservation in Tsavo is further complicated by climate change, particularly recurring droughts that exacerbate water scarcity and vegetation loss. During dry seasons, livestock from neighboring areas often encroach into Tsavo, intensifying competition for limited resources and accelerating land degradation.

“Climate change exacerbates these challenges,” Kamaru explained. “Overgrazing by livestock depletes vegetation, leading to habitat loss for wildlife. This ripple effect strains ecosystems and reduces prey availability for predators like lions.”

Muruthi added, “We must minimize the cost of living with lions for local communities, ensuring a future where lions, their prey, people, and the ecosystem can thrive.”

Collaborative Conservation for a Better Future

Collaring projects like this one in Tsavo are costly but vital for conservation. Kamaru acknowledged AWF’s support in facilitating this work. “Without partners like AWF, securing the resources needed for this research would be incredibly challenging,” he said.

Douglas Kamaru (right) attaches a GPS collar to a sedated lioness in Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, Kenya.

So far Kamaru has successfully collared four lions in the Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary and the surrounding ecosystem. The lions will be monitored for the next two years as part of the research study.

This study has been made possible through the support of the University of Wyoming, Simply Southern, KWS, Wildlife Research and Training Institute (WRTI), Taita Taveta county government, private conservancies, and the local community.

Through initiatives like this, AWF and its partners are not only protecting Tsavo’s lions but also safeguarding the delicate balance of an entire ecosystem.

Watch: A 2021 short film shows what it takes to collar a lion