Empowering communities to halt forest loss in the DRC

The Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex is a place of stunning beauty and rare wildlife in northern Democratic Republic of Congo, but it also faces significant challenges that threaten its continued existence. Deep within the heavily forested landscape, poaching, illegal fishing methods that poison water, artisanal gold mining, and slash-and-burn agriculture are slowly decimating biodiversity, leaving the complex a shadow of its former self.

These practices — sometimes the result of ignorance, sometimes out of attachment to custom — contribute greatly to the destruction of wildlife habitats and the extinction of at-risk species. The Bili-Mbomu landscape is home to the largest population of the endangered eastern chimpanzee and one of the last remaining populations of critically endangered forest elephants in the region.

In response to these challenges, African Wildlife Foundation launched the Community-Based Counter Wildlife Trafficking program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development in 2018 to pilot a resolution approach focusing on community resilience and improved biodiversity protection.

"The program is deployed in three phases, starting with preliminary studies [to] understand key issues in the landscape. Thereafter, we implemented pilot activities for the benefit of communities, and finally evaluated the rate of completion of said activities before proceeding to scale up promising ones," explains Phila Levo, AWF’s Community Development Officer.

Currently, the program is focusing on developing sustainable agriculture, participatory mapping for community land-use planning, and the revitalization of the Local Committee for Conservation and Development. Set up by the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (or ICCN), the committee provides a collaborative structure for partners and the community to work with the wildlife management authority. With representatives chosen by the community, the committee enables people to report issues to the ICCN and allows the authority to develop and communicate suitable resolutions. As Community Facilitator Emile Mbolihinie explains, the aim is to ensure social cohesion and aid development.

"It is true that the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex is a nucleus plagued by several ills. Nevertheless, as a result of the socio-anthropological surveys we have conducted, it appears that slash-and-burn agriculture remains the biggest problem in this protected area," says Antoine Tabu, AWF’s DRC Country Coordinator.

"This type of agriculture is practiced here by the whole community due to ignorance of the way they should cultivate and the harmful consequences [of this method on] nature. That is why we decided to focus our efforts on introducing farmers to sustainable farming techniques," he adds.

AWF donated watering cans for farmers to support their crops during the dry season

Agricultural recovery advances in the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex

The program involves training households in sustainable agriculture, which takes into account the wellbeing of the environment while also boosting productivity to improve the living conditions of communities.

"In order to maximize the chances of success, we started with sensitization. Over 2020, we sensitized 60 households on sustainable agriculture, reaching a total of 540 people. And for 2021, we will increase to 180 households, or a total of 1,620 people targeted," says Freddy Bikanza, who provides agronomic expertise as AWF’s Technical Assistant in the landscape.

The socio-anthropological studies carried out in the region found that improving agriculture within this protected area must involve the provision of upgraded seeds to farmers, as well as the introduction of rotational agriculture and new cultivation techniques. The promotion of business agriculture is also critical in the transition to sustainable agriculture.

AWF helped the farmers repurpose their farms to establish seed fields (covering up to 8 hectares to multiply improved seeds) and farmers' school fields — 1-hectare plots subdivided from a large farm to allow them to practice new cultivation techniques. At the same time, the community has also been trained in promoting agribusiness by picking up skills to support the production, processing, and marketing of agricultural products.

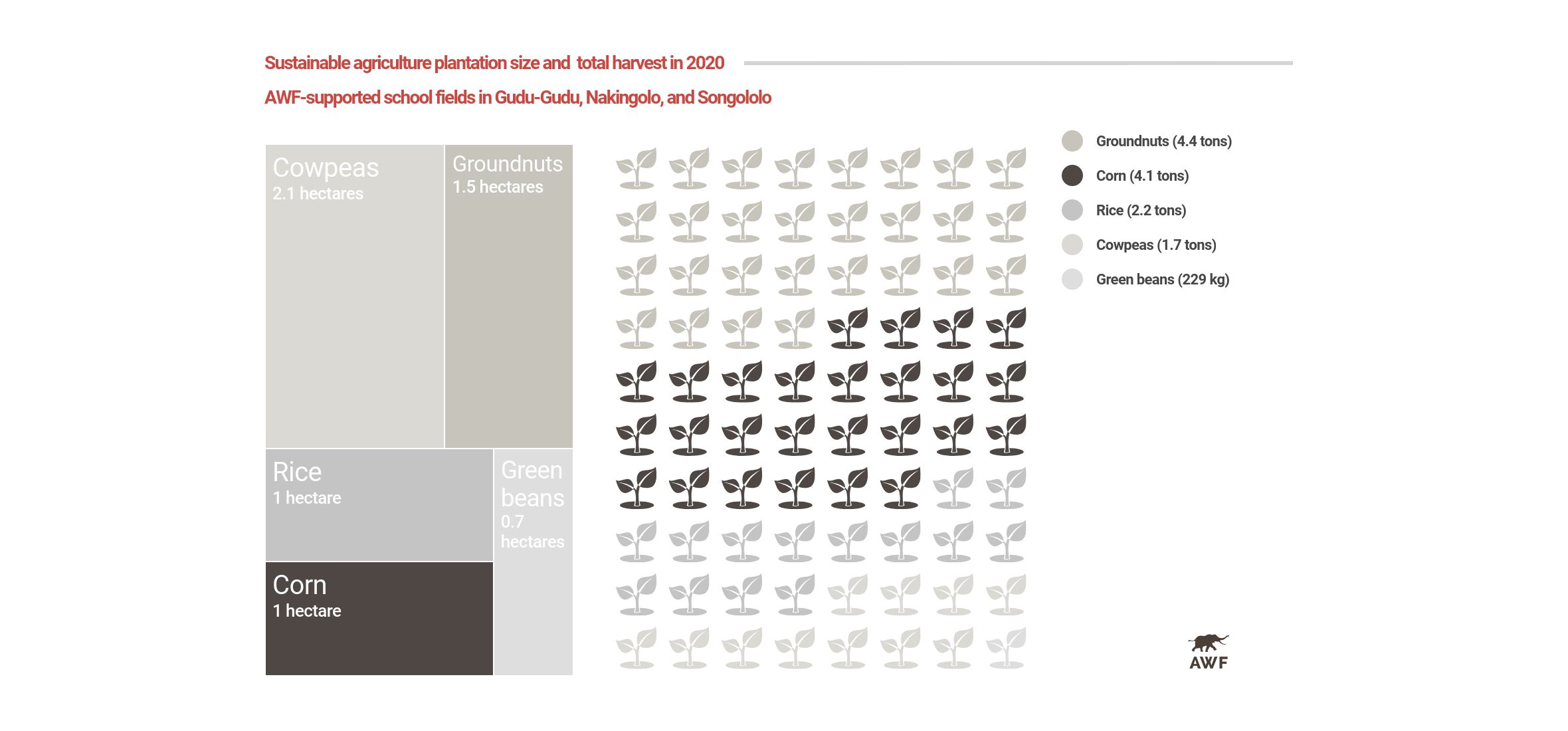

AWF has set up school fields in Gudu-Gudu, Nakingolo, and Songololo for various food crops, including corn, groundnuts, rice, and cowpeas. “In 2020, the farmers harvested 73 kg of soybeans from an area of 67 ares. As for cassava, even though the seeds have not yet reached maturity, we can already estimate the yield of cuttings at more than 60,000 linear meters, or capable of covering 24 hectares of fields during the month of March 2021.”

This significant first harvest has encouraged the local community, which was initially reluctant to adopt new practices.

"When AWF first contacted us, we were not motivated to listen to them because we thought of Bili-Uere as our land, and it is not for a foreigner to come and teach us how to cultivate or manage it. For my part, it was when I saw the quantity of beans produced that I changed my mind. With my one-hectare field, I never managed to produce more than one ton of maize, yet AWF produced more than four tons in a school field of the same size," says Gilbert Dikumbo, head of Nzokumbade village.

AWF's efforts in agricultural recovery are taking the local community of Bili out of their comfort zone and into new areas of knowledge related to environmental conservation.

Farmer Mboli Futilan Brigitte expressed her satisfaction with the services AWF provides her community. "Before, I was not sure how important it is to manage biodiversity resources rationally. Even less that the type of agriculture that we and our ancestors have been practicing for years on our land was the cause of our low yield. I, therefore, thank AWF for this instructive and rewarding learning experience."

Engaging local forest guides in participatory mapping

Sustainable agriculture has been a perfect complement to the participatory mapping activities carried out within the Community-Based Counter Wildlife Trafficking program.

“When the old farming fields allocated in the protected area are abandoned, the forest will grow back, and the damage caused to biodiversity will be repaired,” clarifies Jean-Claude Kalemba, AWF’s GIS Technical Assistant.

He explains the importance of the participatory mapping exercise: “This will allow us to identify and delimit the cultivation areas, monitor their level of use by the community, and discuss with them in a consensual manner in order to arrive at a land-use plan."

Participatory mapping is a process that prioritizes the sensitization of land users and empowers them to make the best decisions about their resources. AWF educates fishers, hunters, and farmers on the benefits of rational land use, visiting village after village to identify the forest guides and train them in the use of GPS and data collection.

Finally, these teams are deployed to the forest to conduct the zoning of activities such as farming, fishing, and gold panning within a particular groupment (a unit of neighboring villages).

The first GPS data collection is intended to mark the boundaries of the land occupied by the groupment before proceeding with a second collection, which will consist of delineating the permanent and secondary forest.

AWF GIS Technical Assistant Jean-Claude Kalemba shares the results of the participatory mapping exercise with Sanza groupment members

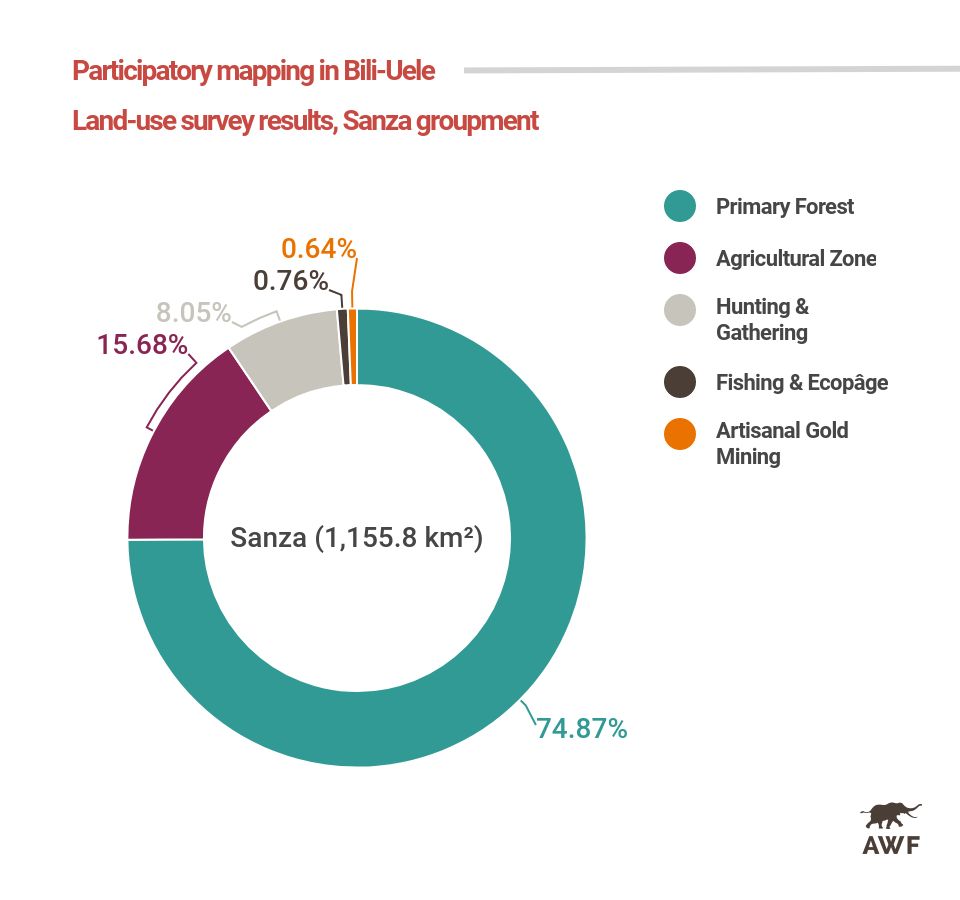

To date, the Community-Based Counter Wildlife Trafficking project has already conducted participatory mapping in the Sanza groupment, and the results have been accepted by Marcel Gbandali, chief of the Gwamangi chiefdom.

"I agreed to validate these results because they are trustworthy, especially since the people who collected them are our village children. Also, it is because I have already understood the merits of the rational use of resources. One day, I do not want my chiefdom, and all the groupments that constitute it, to be poor in resources like those of my fellow chiefs. I, therefore, encourage AWF to continue zoning until all the groupments in the Gwamangi chiefdom are covered," he says.

Vincent Ndulue, one of the forestry guides who participated in collecting mapping data of the Sanza groupment, shared his experience. "The difficulty for us was that at the beginning, the concept of zoning seemed suspicious. For example, I thought that the African Wildlife Foundation, in complicity with the chief, would surely proceed to modify the boundaries of our groupment in order to appropriate a good part of our land. But I understood that zoning has nothing to do with that, which is why I agreed to be part of the data collection team."

The results obtained at the end of the mapping of the Sanza groupment, whose total area is 1,155.8 sq. kilometers, show that the permanent or primary forest represents 74.9 percent or 865.3 sq. kilometers, the agricultural zone 15.7 percent or 181.3 sq. kilometers, the area of hunting and gathering is 8 percent or 92.9 sq. kilometers, the area of fishing and ecopâge is 0.76 percent or 8.8 sq. kilometers, and the gold panning area covers 0.6 percent or 7.4 sq. kilometers.

"The first mapping results presented by AWF have [provided] a global overview of the intact part and the part invaded by anthropic activities. In this way, it will be easier for us to send troops on patrol, targeting specific objectives," said Bernard Iyomi, site manager of the Bili-Uele Hunting Estate, a designated area within the complex.

AWF’s work with communities in the landscape demonstrates that conserving biodiversity does not mean leaving nature's resources untouched. "Rather, it means thinking about methods for the rational use of both wildlife and plant resources. Of course, this is a comprehensive process. Nevertheless, it is already underway and that is what is important," notes Levo, satisfied with the progress of the project.

For the Bili-Mbomu Protected Area Complex and the surrounding communities, he sees a bright and promising future through the Community-Based Counter Wildlife Trafficking project.