Community Conservation: Transforming a Degraded Cattle Ranch into a Thriving Giraffe Nursery and Community-Based Cattle Operation

The people of northern Tanzania and their livestock long ago adapted to living alongside wildlife. For millennia, the Maasai have tracked the movements of wildebeests to identify good grazing; the favorite hideouts of lions to avoid attacks on cattle; and the presence of oxpeckers to know if dangerous buffalo are nearby.

In the past 60 years, however, drastic changes have come to the Maasai Steppe, a large semi-arid grassland ecosystem in north-central Tanzania. Large-scale farms, the expansion of safari tourism, the creation of national parks, and restricted access to once communally used land have squeezed the rangeland available to livestock. With more cattle on less land, grasslands are becoming overgrazed. The spread of human settlements and agriculture have blocked age-old wildlife migration routes, leading to more frequent—and sometimes deadly—confrontations between people and animals. And climate change, which has intensified droughts and upended rainfall patterns, is escalating competition for green grass and fresh water, pushing even more pastoralists to agriculture.

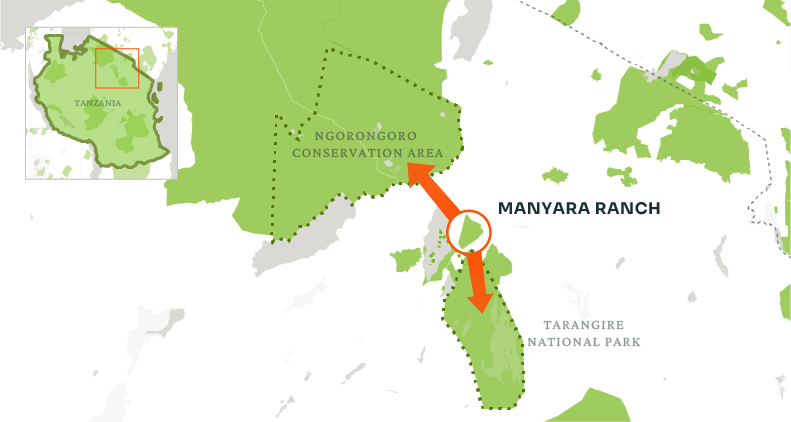

Anchoring the Maasai Steppe are Tarangire and Lake Manyara National Parks, where the shores of the eponymous river and lake abound with wildlife in the dry season. The steppe is home to some of the world’s most abundant and diverse wildlife, including one of the largest—and growing—populations of elephants in Africa (recovering from heavy poaching in the 1970s and 1980s) and the only stronghold of the eastern white-bearded wildebeests. The ability to move between the parks and beyond them into the plains is crucial for the survival of many of the ecosystem’s most iconic species, including elephants and wildebeests. But safe, unimpeded pathways are becoming scarce. In between the two parks, in the all-important Kwakuchinja wildlife corridor, sits a patchwork of villages, farms, large herds of livestock, grasslands—and Manyara Ranch.

Manyara Ranch lies in an important wildlife corridor between two protected areas.

Manyara Ranch is a vital link along one of those migration routes. It helps connect the national parks to each other and to the wet-season grazing grounds of the Northern Plains, described as the “last, best remaining breeding ground” for the ecosystem’s migrating wildebeest, zebras, gazelles, and others. In addition to the migrating animals that seasonally pass through, the ranch today is home to resident giraffes, lions, and many other iconic African species—as well as more than a thousand cattle.

The lease to the land is now held by the Monduli District Council, and the day-to-day running of the ranch is managed by the Manyara Ranch Management Trust, composed of representatives from the Monduli council, two local villages, the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority, and AWF.

“The vision for a project like this is to bring management expertise to the local stakeholders. We want to think inclusively and really focus on creating local partnership in decision-making regarding operations,” said Pastor Magingi, AWF’s Tanzania Country Coordinator.

The Many Iterations of Manyara Ranch

Every season when the rains start, the thousands of wildebeests that congregated in the dry-season refuges of Lake Manyara and Tarangire National Parks depart for the seasonal streams and fresh grasslands of the plains. It’s one of only a few long-distance migrations of large mammals left on Earth. The wildebeests used to have nearly a dozen routes to choose from. Nowadays, all but two have been blocked. With a flourishing savanna, anti-poaching patrols, and manmade water points, Manyara Ranch—cattle, goats, and all—has become an essential respite for migrating wildebeests, a thriving giraffe nursery, and home to zebras, elephants, lions, and more.

Wildebeest run along the life-giving Lake Manyara.

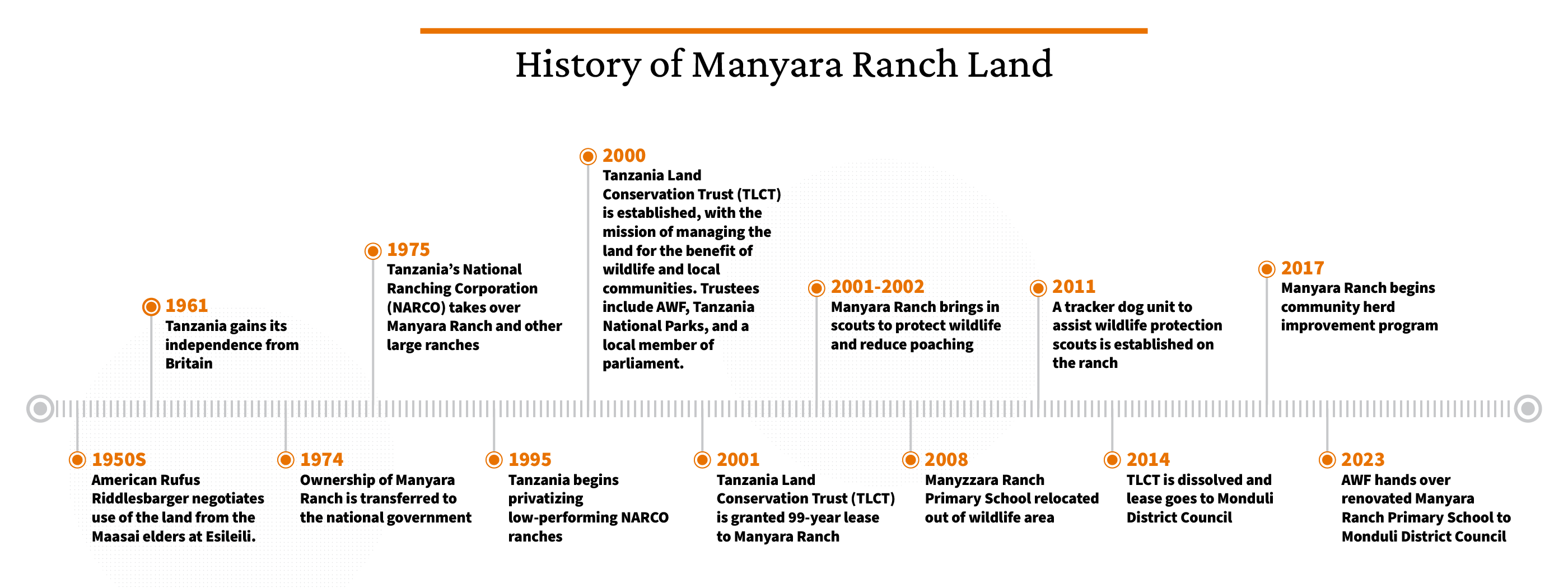

The land was first developed in the 1950s by Rufus Riddlesbarger, an American entrepreneur who moved to what was then British Tanganyika after a string of legal troubles in the United States. He secured use of the land that would become Manyara Ranch from the elders in the nearby village of Esilalei. Because it was overrun with tsetse flies, the Maasai hadn’t grazed their cattle there in years.

The cattle ranch later passed to another immigrant to Tanzania, George Damm. When Damm was killed in 1974, the central government assumed control of Manyara Ranch. Soon after, it and many other large livestock operations fell under the management of Tanzania’s National Ranching Corporation (NARCO).

Like many of the NARCO ranches, Manyara was hobbled by poor management and a lack of resources. It lost money, and its grasslands became barren. Poaching and illegal tree felling for charcoal further eroded the habitat. In 1995, when President Benjamin Mkapa was elected, his vision was to increase the efficiency and profitability of government institutions. Manyara and other underperforming NARCO ranches became targets for privatization.

AWF was active in Lake Manyara and Tarangire National Parks at the time, working with Tanzania National Parks and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to improve infrastructure and management plans. Concerned that the sale of government-held properties would harm wildlife, USAID commissioned a study to understand the potential effects of privatization. The 1998 report concluded that if Manyara Ranch “were to be used for modern ranching or intensive agricultural purposes, the impact on wildlife movement could be extremely negative.” Of the three properties evaluated in the Maasai Steppe, Manyara Ranch “seems to be the single most consequential for wildlife movement.”

Manyara Ranch serves both wildlife and livestock ranchers.

When it became clear the government indeed planned to divest itself of Manyara Ranch, AWF staff in Tanzania began working with local communities, officials in the national government, and other nongovernmental organizations to put together a proposal. The wildebeest migration had persisted this long; it couldn’t be cut off now.

The proposal had two key components. First, instead of a national park with strict limits on human activities, the ranch should become a self-sustaining, multi-use conservancy. While Tanzania had successful examples of community-run wildlife management areas based on ecotourism, this would be a test case for a new conservation model in Tanzania—one in which sustainable livestock ranching, wildlife protection, and tourism could coexist.

The second component was that the land should be held in a trust, with its board managing Manyara Ranch for the benefit of wildlife and local communities.

In 2001, President Mkapa granted the newly registered Tanzania Land Conservation Trust a 99-year lease to Manyara Ranch. Trustees included a local member of parliament; representatives from AWF, Tanzania National Parks, the World Wildlife Fund, the United Nations Development Program; members of the local Maasai community; and a representative from the tourism industry. The lease was transferred to the Monduli District Council in 2017.

A ‘Peaceful Stay’ for Animals

Day-to-day ranch operations have been managed by AWF since 2013. The overgrazed grasslands have recovered, the seasonal migration of wildebeests continues, and with the formation of TLCT, the nearby villages of Esilalei and Oltukai are more closely involved in management than ever before.

When the national government granted the lease in 2001, rehabilitating the land was a priority—a healthy habitat would be the first step toward thriving wildlife, robust livestock herds, and, eventually, tourism. We developed a new general management plan to give overgrazed grasslands time to recover and ensure ranching activities kept a comfortable distance from core wildlife areas. The restoration of dams meant the land could support more animals than before, and the dams’ strategic placement helped prevent wild animals from wandering into human-dominated areas to find water.

Next came safety—for people and wildlife. A crumbling primary school in the middle of the ranch interrupted wildlife movements, and its location meant that children would run into elephants and other wild animals on their way to and from class. It was an unacceptable risk to both their safety and the animals’. The school was relocated closer to the road and social services outside the ranch, and it was fully renovated, including new dormitories for the students, accommodations for the teachers, a computer lab, and more. This relocation also allowed wildlife on the ranch to move more freely. Today, the boarding school is one of the best in the region and has 1,050 students enrolled full-time, many from the surrounding pastoralist communities.

Poaching, too, was a concern. By the end of the NARCO days, it had come to pose a significant threat. Elephants were targeted for the illegal ivory trade, and illicit hunting for wild meat threatened zebras and smaller species such as dik-diks.

“There were no wildlife scouts on Manyara Ranch,” says Magingi. “The National Ranching Company, they don't have those skills. They were just taking care of livestock.”

Canine-and-handler teams track and deter poaching.

AWF introduced scouts to protect wildlife in Manyara Ranch around 2001. Today we contract Honeyguide, an Arusha-based nonprofit, to train and manage wildlife protection scouts recruited from nearby communities. These scouts run anti-poaching patrols in and around the ranch, and maintain a unit of tracker dogs to help pursue suspected poachers.

“The approach here is that you don't need so many scouts,” says Philip Muruthi, AWF’s Vice President of Species Conservation. “What you need is a few who are effective, who are working with the community. When you have community buy-in, you don’t need to take a fortress approach. Scouts are partners with the communities.”

No elephants have been poached on Manyara Ranch since 2015.

Now Manyara Ranch is “a breathing area” for wildlife, says Lota Melamari, a former Director General of Tanzania National Parks and an inaugural board member of the original trust. “Animals can come and experience a peaceful stay before they move to outside areas.”

This is clear from the abundance of wildlife on the ranch today. Manyara Ranch is an important giraffe nursery, with the highest reproductive rate for the species in the entire Maasai Steppe ecosystem. Several thousand zebras and hundreds of gazelles migrate through or reside on the property each year. There are lions, leopards, and hyenas, and every once in a while, staff spot a pack of rare and elusive wild dogs. In August of 2023, four different prides of lions—a total of 27—were sighted at the ranch.

“I’ve never seen so many giraffes as I’ve seen here, and one thing I can say for sure is that their beauty is beyond description,” says Doreen Mungure of the AWF Tanzania team. “Manyara Ranch as their breeding site can leave you in awe as it offers a fascinating opportunity to observe giraffes taking care of their calves.”

Seeking Balance Anew

Predator-proof “boma” fences keep lions away from cattle.

While securing the wildlife corridor is what first drew AWF to Manyara Ranch, cattle have, and continue to be, main characters in the Manyara Ranch story.

This is because cattle are central to Maasai culture. Maasai livelihoods, traditions, and social relationships are deeply intertwined with cattle. A large herd signals wealth and status; wars have been fought over access to grazing land. For more than 3,000 years, the Maasai balanced the needs of their herds with the needs of the wild animals around them.

But as the landscape has become increasingly fragmented, that equilibrium is harder to maintain.

More livestock and less grazing land, for example, are leading to the loss of wildlife habitat. To promote smaller herd sizes, Manyara Ranch runs a community livestock improvement program that emphasizes quality over quantity. Community cattle are mated with the ranch’s own Boran cattle.

“The Boran cattle breed has been found to be fast-growing, fertile, and a good milk producer compared to other indigenous cattle breeds,” Magingi says. Introducing these traits to community herds makes each cow more valuable and smaller herds more viable.

“AWF has provided employment and been running a livestock improvement program for Esilalei village. Also, every year they sell breeding bulls and cull cows at a subsidized price [which] improves the income of everyone who benefits from the program,” says Ormee Shamburi of Esilalei.

Community cattle generally are not allowed on Manyara Ranch’s carefully managed grasslands. But when forage is scarce, local cattle owners can request access to areas of the ranch reserved for community grazing in the dry season. Still, tensions remain over unsanctioned grazing in the fenceless ranch.

Thanks to boma fences, lions can coexist with livestock in Manyara Ranch.

Another challenge to coexistence comes from livestock and wild predators sharing tighter spaces. Whether it’s gray wolves in the United States or African lions in Tanzania, animals that attack livestock often face death themselves. Aside from the monetary loss to the cattle owner and the conservation consequence of losing a top predator, these kinds of conflicts can erode local support for conservation efforts more broadly.

“Predation is there. We have to live with and manage it,” Magingi says. While Manyara Ranch’s cattle are rounded up into a permanent metal corral each night to protect them from lions, most pastoralists outside the ranch rely on less secure, traditional thorn bush bomas. To help protect cattle—and lions—AWF has provided mobile, predator-proof bomas since 2017 for community cattle when they come to the ranch for the breeding program. Outside of the ranch, AWF has provided technical support to help build more than 50 bomas, but current boma programs are led by other organizations.

Lions and Elephants—and Children?

To say the Manyara Ranch Primary School was not in good shape when the trust took over the ranch would be an understatement. The classroom building was missing bricks in the walls, and cracks ran down its sides. In the crowded dormitories, children slept two or more to a bunk bed. And once the sun set, pupils couldn’t leave for fear of running into an elephant or lion.

“The old Manyara Ranch school where I studied was located in a very remote area. Many of us at a young age walked several kilometers [to reach it],” said Lilian Nakuyiet Joseph Loolooitai, who attended Manyara Ranch Primary School from 1989 to 1995 and went on to finish her education with a Masters degree in Agrarian and Environmental Studies from Rotterdam University in the Netherlands. “The school had no communication services and little infrastructure," she said, "and it had no clean water, depending only on open earth dams.”

AWF CEO Kaddu Sebunya visited Manyara Ranch Primary School in late 2023, after AWF handed it over to Monduli District Council earlier that year.

Building schools wasn’t part of the original vision for Manyara Ranch, but it quickly became clear that relocating and improving the primary school was key to both preserving the wildlife corridor and earning community support. In 2008, AWF relocated the school to the edge of the ranch, near the road, where children would be less likely to cross paths with animals. And in 2023, we completed an overhaul of the campus. Funded in part by the Annenberg Foundation and other donors, it encompassed everything from new classrooms, dormitory buildings, and a computer lab to improved outdoor play areas and pathways using local stone and gravel. Once renovations were complete, AWF handed over management of the school to the Monduli District Council.

Today more than a thousand students attend, and the school is considered one of the best in the region. Built into the curriculum: environmental stewardship.

Conservation education has always been a part of AWF’s mission. Back in 1962, a year after we were founded, we funded the establishment of the College of African Wildlife Management, also known as Mweka College, in Tanzania. Today, Mweka students spend time at Manyara Ranch to learn about wildlife and livestock coexistence, community conservation, and human-wildlife conflict mitigation.

‘A Perfect Tourism Destination’

Manyara Ranch is situated along Tanzania’s famous northern safari circuit, which includes Lake Manyara and Tarangire National Parks as well as Ngorongoro Crater and Serengeti National Park, both UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Tourism is the second biggest contributor to Tanzania’s gross domestic product, according to the World Bank, which ranks the country first in Africa for its nature-based tourism resources. Still, there is much room for development and economic growth.

Manyara Ranch’s livestock operation has not yet turned a profit, but the tourism opportunities are immense. Because it is not subject to the limitations of national parks, Manyara Ranch can offer tourists unique experiences such as walking safaris and horseback riding.

From 2009 to 2019, Manyara Ranch hosted a small, high-end tented camp for tourists. “It truly was magical because we had the ranch to ourselves, and the wildlife viewing was really incredible,” says Craig Sholley, a senior vice president at AWF. Just outside the ranch, AWF and USAID supported the development of the Esilalei Women’s Cultural Boma, a small co-op of local Maasai women who sold beadwork and hosted cultural demonstrations for tourists making their way around the northern safari circuit.

While the arrangement with the original tourism operator fell apart, AWF is now working with the Monduli District Council to help identify and directly contract a new operator. The Manyara Ranch management plan recognizes the value of making Manyara Ranch a well-marketed tourism destination. A thriving tourist camp not only would help fund the ranch and its conservation activities, but it also would share revenue with local communities and create jobs in a sustainable industry, showing in concrete ways that wildlife conservation is worth the effort.

“For years, the Maasai community in this area has faced marginalization," said Happiness R. Laizer, District Executive Director (Monduli District, Tanzania). “Nonetheless, this ranch serves as evidence that when provided with opportunities, local communities can effectively conserve wildlife while also deriving benefits from their presence on their lands. This mutual benefit model allows for co-existence reminiscent of our ancestors. AWF envisioned and invested in this journey, and we are thrilled to advance it to the next level with their continued support.”