Agriculture and Conservation Can Be Complementary

AWF works with farmers and commercial agriculture to balance sustainable farming with space for wildlife. The work includes everything from zoning land so wildlife and agricultural development can coexist, to introducing farming techniques that increase crop yields (therefore decreasing the need to clear more land) and deter wildlife from wandering onto cultivated land.

AWF-supported land-use planning is guiding development in Tanzania’s fertile Kilombero Valley, where recently we focused on strategies to protect the region’s essential fresh water, while planting and enterprise strategies further north in Mkomazi have reduced conflict between wildlife and farmers.

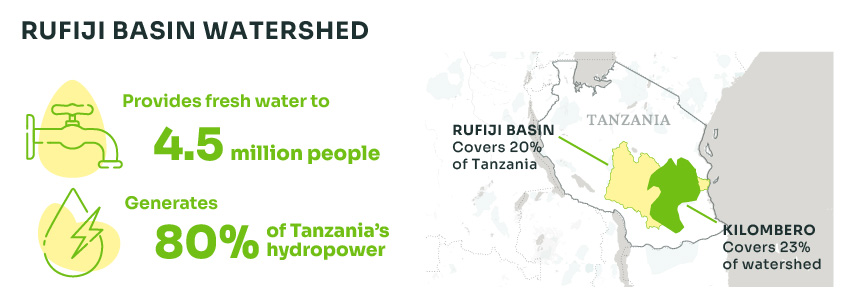

Kilombero is part of the Rufiji Basin watershed.

In Kilombero, water use associations monitor river health to inform conservation action.

Protecting the Richness of Kilombero

Tanzania’s lush Kilombero Valley is part of an important regional watershed, with its rich soils and growing conditions making it ideal for food crops. The valley is in the middle of the country’s Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor, also known as Tanzania’s “bread basket.” The corridor stretches from eastern Zambia to the Indian Ocean in central southern Tanzania, producing more than half of all the food grown in the country. To transport crops like corn, wheat, rice, and sugar, the Tanzanian government has worked with investors like China to build better road and rail systems. Development pressures from agricultural expansion and shifting growing patterns from climate change are threatening the health of the watershed, degrading key rivers like the Mngeta and the Mchombe, and compromising wildlife movement between Udzungwa Mountains National Park and Selous Game Reserve.

Since 2014, AWF has partnered with local communities and commercial agricultural producers to resolve agricultural and biodiversity challenges, supported by funding from DGIS, SIDA, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV)/International Climate Initiative (IKI) through the IUCN, and Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Global Nature Fund (GND). This included facilitating locally-led land-use planning to preserve key wildlife corridors and identify where river restoration can have the most impact. We also expanded farmers’ use of ecologically and economically viable production technologies and improved farmers’ access to financial institutions and markets, maximizing use of the land and reducing the need to clear more for agriculture. Today, farmer coops and grower associations we helped establish are flourishing.

AWF empowers farmers and other local people with the knowledge and tools to manage water catchments Kilombero Valley.

Recently, AWF helped establish water use associations, empowering local stakeholders with the knowledge and tools to manage water catchments, which are areas of land where vegetation collects rainwater to feed the river. Trees were planted to help prevent erosion along river banks, and water use association members were trained to sample and test water health. Looking forward to FY24, we are extending our restoration approach to three village communities in the Great Ruaha catchment, starting with an assessment of the feasibility and appetite for establishing a finance mechanism where upstream communities will be paid for the ecosystem services provided by the river they are restoring.

Helping farmers reduce human-wildlife conflict in Mkomazi

Across the 14 landscapes where we worked in FY23, AWF supported farming initiatives to help manage human-wildlife conflict, including showing farmers how to plant wildlife-deterring crops or place beehives among crops to prevent wildlife from trampling their fields. Due in part to tactics like these, among farmers we partnered with, we measured a 49.2% reduction in human-wildlife conflict in FY23, including a 53% drop in crop destruction.

Tsavo-Mkomazi straddles Kenya and Tanzania.

One example of what this looks like can be found in Tanzania. The Tsavo-Mkomazi landscape in Kenya and Tanzania currently faces challenges with human-wildlife conflict, due in part to the large elephant populations there. It is a landscape where conflict mitigation measures make a difference. Mkomazi is on the Tanzanian side of the transboundary landscape, which becomes known as Tsavo when it crosses into Kenya. In Mkomazi, AWF introduced sunflower farming within existing land use plans, planting the crop strategically around farms because the thorny crop discourages wildlife from passing through it, minimizing the likelihood of elephants or other wildlife wandering onto farmland. Besides reducing the destruction of other crops, sunflower farming offered farmers an alternative income opportunity, as they were able to sell the seeds for cooking oil and sunflower seed cakes to feed livestock. In FY23, one village processed 600 kilograms of sunflower seeds, and the protected farmland had no wildlife incursions. The success has motivated farmers to scale up their sunflower crops.

As another means of managing conflict between farmers and wildlife in Mkomazi, in FY23, AWF provided refresher training for farmers who have installed beehive fences to keep elephants away, protecting 100 hectares and preventing crop damages estimated at 10 million Tanzanian shillings, or about US $4,000. (According to 2018 data from the Food and Agriculture Organization, the average small family farm in Tanzania grosses US $5,000 per year and farms around 1.2 hectares. A hectare is around the size of a rugby field.)