Explainer: What does CITES COP19 mean for Africa’s biodiversity?

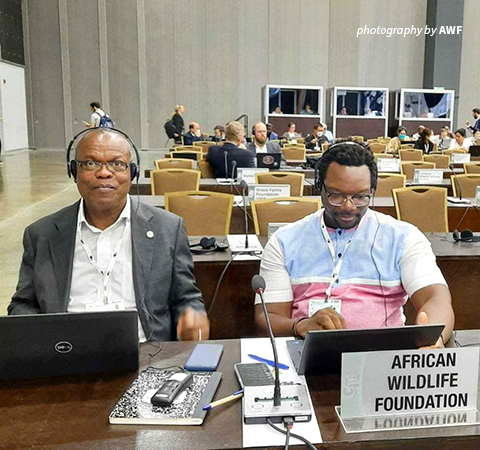

At COP19 in Panama City, Parties endorsed efforts to involve IPLCs in CITES decision making processes. A working group will be engaged through the secretariat

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (or CITES) is meeting in Panama City, Panama from November 14-25, 2022. African Wildlife Foundation’s Vice President, Species Conservation and Science Dr. Philip Muruthi has attended every meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CITES since 1997. He explains why bringing together wildlife range States, wildlife conservation organizations, and community groups from across the world is so important for the sustainable conservation of Africa’s natural resources.

What is the ecological value of monitoring the trade of wild species?

If wildlife trade is managed badly, it is detrimental to the long-term survival of species. Even before the 1960s, people had noticed that legally traded plant and animal species were diminishing because trade was occurring at volumes that could not be sustained. With time, it became clear that unregulated trade could potentially become a major threat to species, and even lead some to extinction.

Looking at the factors driving African wildlife population declines comprehensively, we know that trade is not the only one; there are various urgent threats facing African wildlife and natural ecosystems. We have to limit habitat degradation caused by climate change. We also must prevent wildlife from being killed in retaliatory attacks while others die from disease due to increased interaction with humans. We also need to develop cross-cutting interventions to get some wildlife species out of a poaching crisis.

What is CITES?

CITES was discussed in Washington, D.C. in 1973 by 80 countries and came into force two years later. There are now 183 member States (referred to as ‘Parties’) that have signed the international agreement and 35,000 species monitored through the convention. A signing Party joins the convention voluntarily and makes a commitment to adhere to its provisions.

Regional organizations, including wildlife conservation organizations like AWF, also participate in CITES. They play a critical role in the convention as ‘Observers’ although they do not get a decision-making vote, which is a function left to Parties only.

How does conservation science inform CITES decisions?

Although CITES regulates trade, it is a science-based convention. It categorizes various plant and animal species based on their levels of endangerment. The most severely affected species faced with the risk of extinction are listed in Appendix I, under which all international trade for commercial purposes is prohibited. Species in Appendix II are not close to extinction, but trade is monitored to ensure that it does not become a threat. The two appendices are the most important. If a Party proposed to upgrade a species to Appendix I, it has to meet certain scientific criteria to justify the trade restriction, such as population decline or extinction in the wild.

What happens at the CITES conference?

Every two to three years, the convention meets at the Conference of Parties to amend appendices and, importantly, assess CITES mechanisms and operational frameworks to ensure the convention is working towards the reason it was established — conserving species sustainably; ensuring that trade is not detrimental.

As voting members, Parties speak first but Observers can signal their willingness to contribute to the discussion. AWF has been an Observer at CITES since 1989 and has joined working groups with other non-voting members from civil society groups to move deliberations forward. Members work closely with the Secretariat to evaluate the various relationships between CITES and other multilateral treaties like the Convention of Biological Diversity, the Convention of Migratory Species, communities, and the private sector.

What challenges do range States face in managing the trade of their wildlife populations?

It is difficult for range States to manage wild fauna and flora if they lack scientific and trade data. A non-voting member like AWF can help Parties to get the best scientific information so they can judge the levels of endangerment and assess the association with trade and a species’ population status. without this technical and financial capacity, Parties struggle to use CITES properly as a mechanism for wildlife conservation and natural resource management.

Listing a species on a CITES appendix does not mean that it is going to be safer; implementation is very important, and it depends on a continental strategy for Africa’s most threatened wildlife species.

Vice President, Species Conservation and Science Dr. Philip Muruthi (left) and Director, Global Leadership Edwin Tambara are representing AWF at CITES COP19

How does AWF contribute to the conservation of wildlife species through a multilateral agreement like CITES?

Collaboration between African countries is critical because a lot of the continent’s wildlife species are transboundary as are key threats like poaching and trafficking. The aim of African conservationists and governments is to conserve viable and functional populations of wildlife species — this is common across the board. Apart from encouraging Parties to support the African Group of Negotiators, AWF urges national governments and members of CITES to utilize science in their proposals and maintain transparent implementation and reporting structures.

AWF champions the African voice for wildlife — we are saying that Africans must speak and act for wildlife. Africans must have a common voice for wildlife and wild lands to thrive in Africa today. A very important role that AWF can play is getting African range States to speak with one voice to help bridge the divide and align their different interests. Countries could walk out of the convention if they feel that non-advocates for trade are infringing their rights and their country sovereignty — this division is not good for continental populations and we must avoid it.

At the same time, AWF advocates for a people-centered approach to conservation and promotes the 2022 IUCN Africa Protected Areas Congress Kigali Call to Action for People and Nature in our deliberations at CITES COP19.

How do the decisions from CITES COP19 in Panama City impact conservation?

As a mechanism for conservation, CITES decisions are quite important. For instance, the transfer of all species of pangolin — which is the world’s most trafficked mammal — to Appendix I at CITES COP17 in Johannesburg in 2016 was a big win for the species and the convention itself. It sent a clear, unambiguous message that international cooperation can save threatened wildlife species before it is too late.

Addressing trade should always be within a framework that includes other key threats to biodiversity, including habitat loss and fragmentation, and accounts for sustainable use of natural resources.