Seeing Quadruple? Discovering Four Giraffe Species

If you’ve seen one gangly giraffe, you might think you’ve seen them all, with their lanky legs, patched coats and famously long necks. New evidence released this month, however, points to the contrary. Africa seems to have four different species of the world’s tallest land mammal.

Historically, scientists believed there was only one species of giraffe, with nine subspecies scattered across the continent. But through the most comprehensive study of these animals to date, researchers uncovered data suggesting giraffes should be categorized into four distinct species: northern giraffe, southern giraffe, Masai giraffe and reticulated giraffe.

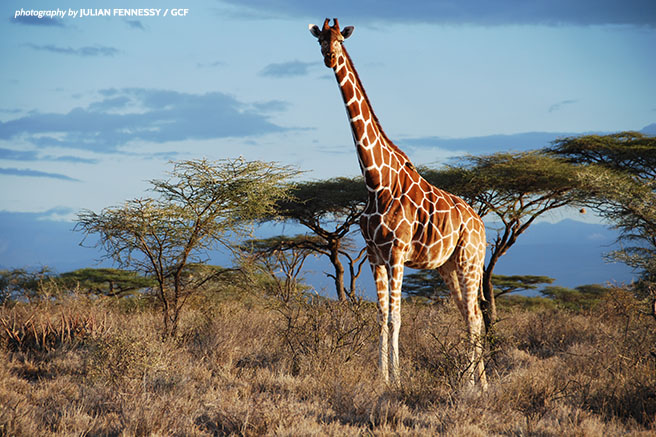

The study is the result of a collaborative effort between the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) and Dr. Axel Janke of Germany’s Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre. “I approached Dr. Janke five years ago to help with genetic testing on giraffe. I was interested in knowing if genetics would help to answer some critical conservation concerns,” says Julian Fennessy, co-director and co-founder of GCF.

Fewer than 8,700 reticulated giraffe remain in the wild, ranging from northern Kenya to parts of Ethiopia and Somalia. The brown-orange patches on their coats are defined by thick, striking white lines that often continue down their legs.

Fennessy says that giraffes have been “forgotten giants” when it comes to scientific research: “In contrast to elephant, lion, rhino and gorilla, there has been relatively little research on giraffe. No one has questioned the old classification system. With giraffe numbers declining rapidly across Africa, we thought it critical to understand how similar, or not, the different giraffes are in order to ultimately help their long-term conservation.”

What the researchers found led them to believe “there had to be more to the story of giraffe evolution,” he says.

Species vs. subspecies

The distinction between a species and subspecies is rooted in genetics. While the subspecies label denotes consistent, but relatively minor genetic variance between groups of the same species, the distinction of a new species arises out of genetic disparities so significant that individuals of different species cannot breed and produce viable offspring. In other words, a species’ gene pool is entirely unique to that group of animals and cannot be recreated from any other creatures on Earth.

Masai giraffes are considerably darker than the other three species. The jagged-edged patches on their coats are separated by irregular, creamy brown lines that continue down below the knee. Clusters of Masai giraffe are scattered throughout parts of Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya.

“Dr. Janke had rarely seen such a large amount of genetic differentiation within a species,” Fennessy explains, referring to their research. “The findings suggest that genetic exchange is rare or can be excluded between the four species.” According to Fennessy, the genetic isolation between each of the four groups hence defines each as its own species.

For this study, the GCF team collected tissue samples from 190 wild giraffes. These were obtained by remote biopsy darts—darts that immediately pop off the animal after impact, taking a small piece of tissue with them. This method ensured the giraffes didn’t need to be sedated in anyway, with the animals only experiencing something Fennessy likens to a mosquito bite.

The samples collected by GCF over 15 years included tissue from all major giraffe populations across Africa, representing each of the nine subspecies considered to exist at that time. This is the first study to ever accomplish such a feat. The study’s results must next be evaluated by IUCN for official recognition of the proposed four-species delineation.

With fewer than 4,750 individuals remaining, the northern giraffe is the rarest of the four species. This species contains three subspecies: the Kordofan giraffe (found predominantly in Cameroon, Chad and the Central African Republic), the Nubian giraffe (which ranges throughout parts of South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia), and the West African giraffe (found exclusively in Niger).

Enabling a targeted approach

It might seem like differentiating between one species and four all comes down to semantics. But, this new giraffe delineation actually has significant implications for conservationists.

Across the continent, giraffe numbers had already been experiencing a worrying decline. And in the study’s 15-year span, the number of giraffes in Africa dropped from an estimated 140,000 individuals to less than 100,000. The new species classifications bring greater clarity to the potential loss of important genetic diversity. “Out of the four newly recognized species, the northern giraffe number fewer than 4,750 individuals in the wild, and reticulated giraffe number fewer than 8,700. As distinct species, it makes them some of the most endangered large mammals in the world and of high conservation importance,” says Fennessy.

Unlike the other three species of giraffe, the southern giraffe population is on the rise. The Angolan giraffe, a subspecies on the southern giraffe, is predominatly found in Namibia and Botswana. Meanwhile, the South African griaffe, another subspecies, ranges throughout parts of Botswana, Zimbabwe, Angola, Zambia, South Africa and Mozambique.

In contrast, the researcher points out, southern giraffe numbers are increasing across Southern Africa. By recognizing the distinct gene pools at risk and identifying which ones are closest to the brink of extinction, the results of Fennessy and Janke’s study enable the conservation community to better understand where and how quickly it should be directing its efforts.

“The research conducted by Drs. Fennessy and Janke has brought truly important information to light,” says Philip Muruthi, AWF’s vice president for species protection. “Giraffes are key species in many of the landscapes where AWF works. We’ve known that human-wildlife conflict and habitat fragmentation have presented serious threats to giraffe survival, but additional knowledge about the extent of the threats to different populations enables us to allocate our resources in a much more targeted, efficient manner.”